Inventing Nature

You might never have heard about him, but without this eighteenth century genius, environmentalism wouldn’t exist, and neither would Earth Day

Happy Earth Day, everyone. Whether you plan to spend it picking up other people’s garbage, planting trees or even partaking of Surrey’s Party for the Planet, it’s sure to be one of those slightly earnest and somewhat boring endeavours made famous by the likes of Greta Thunberg. She seems to have fallen by the green wayside recently, replaced by the global Money Mafia, who have hijacked the green narrative to serve their own nefarious ends. We no longer argue about whether we are responsible for Climate Change; we have moved on to fighting about who gets to profit from our increasingly chaotic attempts to wean ourselves off the infernal combustion engine, overconsumption, international travel, food, warm houses, and so on. We can’t seem to agree on the most basic things, like how wind, solar and nuclear power is in any way ‘better’ or more ‘sustainable’ than oil and gas. The green agenda and the very language we use to describe it, has serious cracks. If you dare to point them out, as Michael Moore did, with Planet of the Humans, god help you.

Which leads me to ask, is there anyone who might hold up as an actual role model for the scarred and besmirched environmental movement? There is, people, there is. His name is Alexander von Humboldt, and he wasn’t just the most famous scientist and explorer of his age; he was also a great humanist, an inspiration and educator of the great as well as the great unwashed, a fighter for the abolition of slavery in the US and a personal friend of Jefferson. He was also gay. His greatest achievement was his ability to envision Nature not as a random collection of rocks, animals, and plants but as an intricate, alive feedback system in which everything is literally connected to everything else. And that man’s ‘mischief’ like our habit of chopping down entire forests, leads to serious problems like erosion and floods.

Honestly, I can’t imagine a more perfect environmental hero for our wokish, anxious and bedevilled age. Let’s have a look at his life so you can decide for yourself.

It’s 1776, and in a small castle in Tegel, on the outskirts of Berlin, two brothers aged nine and seven, are getting the tutorial treatment from a tall, thin, big eared martinet never satisfied with his pupils, Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt. His name was Gottlob Johann Christian Kunth, not only the tutor but the lifelong major-domo of the aristocratic von Humboldt family. They esteemed him so much that he is buried in the large park surrounding the Schloss, and in 2010, I journeyed there to pay my respects. Because Kunth was none other than my great- great-great- grandfather. As a former tutor back in the nineties myself, I was thrilled to discover that tutoring ran in my family though my style of tutoring can only be described as the opposite of Kunth’s so it could hardly be genetic.

That was a relief. Because he was a not a nice man. Still, it’s fascinating to meet one’s ancestor in books. My favourite portrait appears in Daniel Kehlmann’s 2006 satirical bestseller, The Measurement of the World, an irreverent tale featuring Alexander, the mathematician Gauss and Kunth. It is a hilarious romp in which nobody gets the respect they are used to as icons of the Enlightenment. Kehlmann describes Kunth as someone who regarded the education of the brothers as ‘an experiment’. But with a definitive objective: one of them was to be a Man of Letters, the other a Man of Science. The decision as to who was going to be which might be decided by tossing a coin, he thought.

That is just one of the many bizarre events and characters in the novel. But they can be checked against a serious biography of Alexander v Humboldt by the historian, Andrea Wulf. In another bestseller, The Invention of Nature, Alexander v Humboldt’s new world, published in 2015, she agrees with the novelist about most details of how the brothers were educated. From a modern perspective, it was more torture than education. Since their father had died young, only Elizabeth, their emotionally distant and cold mother, and Kunth were left to raise the boys. In spite of their high social status and wealth, theirs was a lonely and austere existence, as Wulf describes it:

…they sometimes searched for a father figure, and JGC Kunth, who oversaw their education for many years, taught them with a peculiar combination of expressing displeasure and disappointment while at the same time encouraging a sense of dependency. Hovering behind them and watching over their shoulders as they calculated, translated Latin texts, or learned French vocabulary, Kunth constantly corrected the brothers. He was never quite satisfied with their progress. Whenever they made a mistake, Kunth reacted as if they had done so to hurt or offend him. For the boys, this behaviour was more painful than if he had spanked them with a cane. Always desperate to please Kunth…they had felt a perpetual anxiety to make him happy.

And while Wilhelm managed to please, Alexander was such a poor student that …his tutors were doubtful that even ordinary powers of intelligence would ever be developed in him.

To make matters even more daunting, the family practised a kind of emotional austerity devoid of any kind of emotional expression. Joy and laughter were verboten.

All this went on relentlessly, twelve hours a day, every day. In addition, Kunth made the boys write stilted letters to important public figures, and invited even Frederick the Great to the castle, there to have serious conversations with his charges. It was always Wilhelm who shone on these occasions while his brother Alexander grabbed every opportunity to escape the dreary atmosphere of the Schloss by roaming out in the woods, collecting frogs and plants while keeping meticulous notes on what he collected. As a young adult he studied mining to please his mother and became one of the youngest mining assessors serving the Prussian State, but against his mother’s wishes, he also continued his habit of scientific exploration that grew into his epochal journeys into Central and South America, Cuba, the nascent USA and finally, Russia.

But he wasn’t just a scientist who ‘invented nature’; he was one of the last polymaths who was able to straddle the enduring divide between science and the humanities. To him, science was not simply about collecting data; it was about understanding and experiencing, about an almost poetic immersion in nature’s secrets. He inspired even Goethe who claimed that one day in Humboldt’s company was more invigorating and instructive than years of reading.

Darwin, forty years younger, avidly consumed Humboldt’s numerous books in which he describes his explorations and discoveries. He told anyone who cared to listen that without those books, he would never have gotten onto the Beagle, nor able to develop his theory of evolution. When Darwin finally met his hero as an old man, he wished fervently to have a serious exchange of views. What he got was wiry, somewhat stooped but still vital old man who wouldn’t let him get a word in edgewise. Humboldt talked incessantly, and he did this with everyone, even at court. His verbal flow, sometimes laced with barbed observations on his fellow man, never ever stopped. And after a while, everyone simply shut up and listened.

Still, he became the most famous and adored man of the age. His correspondence with everyone who mattered ran to thousands of letters every year. But he was no elitist: his books and his free lectures were read and avidly consumed even by the so-called common people. He was committed to communicating with everyone, not just his peers. Living a rather unpretentious life in a rented flat overflowing with books, papers and scientific instruments, H never got rich; money wasn’t important to him. When he came back from his last big exploration that took him across all of Russia at the Tsar’s expense, he returned the money he had not spent and said it should be given it to ‘another scientist who needed it’. He was forever lending money to destitute fellow scientists when he himself had debts. Which leads me to think that we should never listen to what tutors and educators say about their charges.

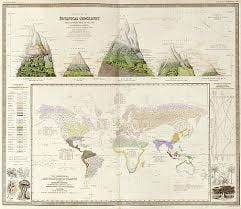

Humboldt’s list of discoveries is prodigious; among them the magnetic pole, electric eels that can kill a man, and proof that the interior of the earth consists of molten lava, not the ice-cold rock beloved of all followers of the then reigning belief called Neptunism. He also made major contributions to our understanding of weather systems because he was the first scientist to describe how ocean and air currents interact. And how bands of temperature that girdle the globe foster similar vegetation. What he understood is that nature is a system, an elaborate tapestry where everything connects to everything else. And that man is embedded in this as much as all other forms of life.

This was a revolutionary concept and I believe it still is. Allow me to elaborate. Our current obsession, far from living in harmony with Nature is to control, manipulate and exploit her for our own ends. This is what Silicon Valley is about, where they are proud to be able to ‘move fast and break things’. You could say that our obsession with exploiting Nature is indeed breaking things, at an increasing rate. You could even argue that the global response to the pandemic is an example of wrongheaded, draconian efforts at controlling a virus that has so far eluded all our best efforts to eradicate it. China’s current obsession with ‘zero Covid’ has jailed millions of people in their homes and it is a perfect example of this mindset. We haven’t done this—yet. But we worship icons of ‘progress’ like Elon Musk, who are at the forefront of a transhumanist agenda that would have us become serfs in a digitized world of surveillance capitalism where algorithms ‘know you better than you know yourself’, to quote the historian Yuval Noah Harari. We’re not making noticeable efforts at following Humboldt’s vision; we’re doing the opposite. The entire Great Reset agenda is driven by this idea that we are in charge of Nature, not the other way around.

The few voices speaking Humboldt’s language without even knowing about him are few in number. The Black Mountain Collective in Britain is one. Charlene Spretnack is worth reading on ‘Techno Utopianism and the Fate of the Earth’. She gets it and even if she has never heard of Humboldt; she is one of his disciples.

The amusing but highly influential Indian sage calling himself Sadh Guru, is another. He is one of a handful of people mobilizing and promoting the idea that saving the health of our soil is urgently needed if we want to survive as a species on this planet. Humboldt would agree. He is doing more for the actual environment than all the clever ‘official’ environmentalists put together.

Alexander von Humboldt died world renowned, close to the age of ninety on May 5, 1859, in Berlin. Kaiser Wilhelm himself proclaimed him to be ‘the most important man since the flood’, and everyone agreed. They gave him one of the most splendid funerals ever seen, attended by everyone from the Royal Household on down to the throngs of people lining the streets of the funeral procession. He was buried at the Schlosspark Tegel, not far from his demanding tutor, Kunth, where we began this story.

Wulf claims that Alexander von Humboldt is the true father of environmentalism, but I believe that we no longer respect his vision of a dynamic, alive earth, a Mother Earth. I do agree with her assertion that one of the main reasons he is not a household name is due to the vilification of everything German during and after WW2. Since we are doing the exact same thing today, vilifying everything Russian, I can only say, we seem to have learned nothing at all. In spite of constant pressure to be a courtier in Berlin, Alexander managed to live most of his life in Paris, explore the globe and stay clear of Prussian nationalism, Napoleonic wars, and the hubris of the court. In sharp contrast, the western world at this very moment, is all too happy to fall into a mindset Humboldt abhorred. One that exalts militarism, war, propaganda and narrow-minded bigotry. It’s something to ponder on this Earth Day, however you choose to spend it.

Thanks for your comments, Geoff. Yes, please, can we make more people like this instead of the narrow specialists running the world just now...

Excellent article, Monika. I’ve come across Humboldt’s name for years, but it wasn’t until I read a lengthy piece in the NYRB that I understood his true importance in the history of science. “To him, science was not simply about collecting data; it was about understanding and experiencing, about an almost poetic immersion in nature’s secrets.” Yes. I recently picked up a biography on another mostly forgotten but once enormously influential German naturalist, Ernst Haekel. We need more naturalists, unlike specialists “who know more and more about less and less”!